| Panayiotis G. Skordi, PhD | ORCiD | California State University, Fullerton |

I have no known conflict of interest to disclose. The study received ethical approval from the Institutional Review Board at California State University, Fullerton (HSR #18-19-287) and was determined exempt under the Revised Common Rule. All participants provided informed consent prior to participation. The author would like to thank the students and faculty of California State University, Fullerton, for their participation and support of this research project.

Applying Kimberlé Crenshaw’s (1991) framework of intersectionality—which highlighted the compounding effects of intersecting social identities—this study examined how the convergence of age and ethnicity shaped achievement in a quantitative gateway course, centering structural equity rather than individual deficits. Guided by a critically-quantitative stance and Community Cultural Wealth (Yosso, 2005), the study analyzed disaggregated achievement patterns by age × ethnicity among students in a required business statistics course. Results indicated that while older students generally outperformed younger peers, this advantage was powerfully moderated by ethnicity, underscoring the compounding impact of intersecting identities: it was strongest for White and Asian students and virtually disappeared for African American students. These findings revealed how racialized opportunity structures mediated the academic return on age-linked experience. This study argued for a transformative justice approach in gateway courses, one that moved beyond monitoring gaps to actively dismantle the structural barriers that caused them.

Keywords: intersectionality, nontraditional students, racial differences, cultural capital, educational equity, postsecondary education, academic achievement

The demographic landscape of higher education was undergoing significant transformation, with increasingly diverse student populations reshaping the traditional undergraduate experience (Choy, 2002; Harper & Simmons, 2019). In particular, age and ethnicity had emerged as pivotal dimensions shaping students’ engagement, resilience, and academic achievement (Bye, Pushkar, & Conway, 2007; Museus & Quaye, 2009). As institutions articulated commitments to diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI), understanding how these demographic factors influenced achievement—especially in quantitatively intensive gateway courses—became increasingly important (Chen, 2013; Lubienski, 2002).

Age-related diversity has expanded across universities as growing numbers of non-traditional students—typically those aged 25 and older—enroll alongside traditional-age students entering directly from high school (Choy, 2002). Prior research consistently finds that older students often demonstrate stronger academic persistence, self-regulation, and life-experience—based coping strategies, which may translate into favorable academic outcomes (Bye et al., 2007; Kasworm, 2010). Yet these advantages are not uniform across settings or student groups, and empirical studies rarely consider how age interacts with other salient identities, such as race and ethnicity.

Simultaneously, ethnic diversity on university campuses has increased, but longstanding achievement disparities persist across racial and ethnic groups (Gonzales, 2015; Harper & Simmons, 2019). These disparities are particularly pronounced in mathematically rigorous or quantitatively oriented courses, where systemic barriers—including differential prior preparation, stereotype threat, and cultural mismatch—can depress performance among minoritized students (Steele & Aronson, 1995; Museus & Quaye, 2009). Although a substantial body of scholarship documents racialized achievement patterns, this literature typically treats age as a neutral or irrelevant factor, missing potential interactions between students’ life stage and ethnicity.

Despite growing recognition that students’ identities are multidimensional, research examining the intersection of age and ethnicity in higher education remained extremely limited (Ryu, 2010; Kasworm, 2010). Studies on non-traditional students tend to treat older learners as a monolithic group, giving little attention to the role of race or cultural context in shaping their experiences. Conversely, research on racial/ethnic disparities rarely explores whether the effects of race differ for younger versus older students. Prior work suggested that age-related advantages could be amplified or diminished across racial groups due to structural inequities (Posselt & Grodsky, 2023). As a result, the educational experiences of older students of color—who navigate both age-related and racialized institutional dynamics—are largely invisible in existing quantitative scholarship.

While prior research has discussed potential psychological mechanisms such as resilience and motivational beliefs, the study’s primary theoretical grounding—intersectionality and Community Cultural Wealth—is articulated in detail in the Methods section alongside author positionality, consistent with reviewer recommendations.

Guided by this multi-dimensional perspective, the study posed two research questions:

It was hypothesized that older students would, on average, outperform younger peers due to greater academic resilience, and that racial/ethnic disparities would emerge consistent with prior research. However, the key expectation was that the benefits of older age would not be uniform across ethnic groups, revealing intersectional patterns masked by single-variable analyses.

Using ANOVA and regression models with interaction terms, the study analyzed performance data from 384 undergraduate students enrolled in a gateway quantitative course at a large public university. By integrating age and ethnicity within the same analytical framework, the study contributes to equity-focused research by illuminating how demographic identities intersect to shape students’ academic trajectories. This intersectional approach moved beyond traditional “gap-monitoring” to consider the structural and contextual factors that produce inequitable outcomes in quantitative disciplines.

This study was conducted from a critically-quantitative perspective that emphasized equity and an anti-deficit approach in quantitative analysis. In practice, I adopted a critically-quantitative stance that foregrounded disaggregation and interpreted any performance differences as reflections of structural contexts rather than individual shortcomings (Solórzano & Yosso, 2002). An intersectional lens (Crenshaw, 1991) guided my approach, acknowledging that age and ethnicity intersected to shape educational experiences. I also drew on Community Cultural Wealth theory (Yosso, 2005) to highlight the assets (e.g., navigational and aspirational capital) that students from diverse backgrounds brought to the classroom—particularly the strengths of older students of color that institutions might have overlooked.

The author’s positionality as a quantitative education researcher committed to social justice informed all methodological decisions. This commitment influenced how variables were operationalized and how results were interpreted, always with an emphasis on uncovering structural opportunities for improvement. In line with this critical orientation, the study’s design and analysis aimed to identify institutional barriers and supports rather than attribute disparities to student deficits. Given this orientation, the methodology emphasized equity at each step. The following sections describe the study’s participants, measures, procedures, and data analysis.

This study was guided by an explicitly critical theoretical orientation that shaped both the analytic approach and the interpretation of findings. Two complementary frameworks informed the work: intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1991) and Community Cultural Wealth (CCW) (Yosso, 2005). Together, they provide the structural lens through which academic performance patterns were examined and contextualized.

Intersectionality posited that social identities such as age, race, and ethnicity do not operate independently but instead intersect to produce unique configurations of advantage and oppression (Crenshaw, 1991). Rather than treating age and ethnicity as additive or isolated demographic variables, an intersectional framework recognizes that students who occupy multiple marginalized identities—including older students of color—may encounter compound forms of inequity not captured in single-axis analyses. Prior research has noted that educational disparities often arise from the interaction between multiple structural forces (e.g., racism, ageism, institutional norms), yet quantitative studies rarely examine these intersections directly (Posselt & Grodsky, 2023). Applying an intersectional lens therefore allowed this study to foreground the complex, layered dynamics shaping performance in a gateway quantitative course.

Aligned with this structural perspective, the study also drew on Yosso’s (2005) Community Cultural Wealth (CCW) framework. CCW rejected deficit narratives about racially minoritized students and instead highlights the forms of cultural, navigational, familial, and aspirational capital that students develop through lived experience. For older students of color, these assets may include resilience cultivated through navigating work, family, and prior schooling contexts; problem-solving skills acquired through adulthood responsibilities; and strong community networks that support persistence. However, traditional academic structures often fail to recognize or reward these strengths (Solórzano & Yosso, 2002). Integrating CCW allowed the analysis to interpret academic patterns not as reflections of individual shortcomings but as indicators of how institutional systems differentially respond to students’ diverse capital.

Guided by intersectionality and CCW, the study employed a critically-quantitative approach that emphasized disaggregation, context, and structural explanation. Rather than assuming that demographic variables reflect inherent abilities or fixed traits, the analysis treated observed group differences as signals of broader racialized and age-stratified opportunity structures (Harper, 2012; Posselt & Grodsky, 2023). This orientation informed the decision to test interaction terms between age and ethnicity and to interpret significant differences through a structural, equity-minded lens.

As a quantitative education researcher committed to social justice in higher education, my positionality shaped the methodological and interpretive decisions in this study. My experience teaching large, diverse undergraduate quantitative courses provided firsthand insight into how structural factors—such as inequitable prior preparation, stereotype threat, and constraints faced by working adult learners—manifest in classroom performance. This perspective informed the choice to adopt an anti-deficit framework, prioritize disaggregated analyses, and center the assets students bring rather than their perceived limitations. While the analyses relied on statistical rigor, the interpretation of findings was grounded in an explicit commitment to equity, consistent with critical race methodology (Solórzano & Yosso, 2002).

The study sample consisted of 384 undergraduate students enrolled in a required Business Statistics course at a large public university in the western United States. Data were collected across two academic years, spanning four consecutive semesters, ensuring that multiple student cohorts were represented. Participants included students from a range of majors, as Business Statistics was a core requirement across several business-related programs.

Demographically, the sample reflected the institution’s broader diversity profile. In terms of age, approximately 74% of participants were traditional-age students (18-24 years old), while 26% were classified as non-traditional students (25 years or older) at the time of enrollment. Ethnically, the sample included students identifying as Asian (32%), White (30%), Hispanic/Latino (26%), African American (6%), and other ethnicities (including multiracial and Native American, totaling 6%). Gender composition was relatively balanced across the sample, though gender was not a primary variable of interest in this study.

Participation in the study was voluntary, with no incentives provided. Student confidentiality was maintained through anonymized dataset handling. The study was reviewed and determined to be exempt by the Institutional Review Board (RIB).

Three key constructs were measured in this study—age, ethnicity, and academic performance—with prior GPA recorded as a covariate. Each was defined and operationalized below.

Age: Students self-reported their age at the time of enrollment. For analytic purposes, age was treated both as a continuous variable and as a categorical variable with two groups: traditional-age students (18-24 years) versus non-traditional-age students (25 years and older). This categorical split aligned with standard definitions used in higher education research (Choy, 2002; Kasworm, 2010).

Ethnicity: Students selected their ethnic identity from institutionally standardized categories. For analysis, ethnicity was operationalized as a categorical variable with the following groups: Asian, White, Hispanic/Latino, African American, and Other. Given sample size considerations, the “Other” category combined multiracial and less-represented ethnic identities. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to ensure that this aggregation did not distort the overall findings.

Academic Performance: Academic performance was measured by students’ average exam score across three midterms and one cumulative final exam in the course. Each exam score was standardized on a 20-point scale for consistency. A student’s average exam score was calculated by summing their exam points and dividing by the total number of exams taken.

Covariates: Given that prior academic achievement is a strong predictor of course performance, each student’s cumulative GPA at the start of the semester was recorded as a potential control variable. However, to avoid redundancy with the broader constructs under investigation (resilience and cultural expectancy-value factors), GPA was utilized only in supplemental robustness checks rather than as a primary covariate in the main analyses.

Procedures: Data collection relied on existing institutional records and careful data cleaning to ensure a valid analytical sample. Specifically, archival academic records and demographic information were obtained from the university’s registrar and academic affairs databases as the primary data sources. After compiling these records, standard data cleaning procedures were applied. Cases with missing values for any key variable (age, ethnicity, or exam scores) were removed from the dataset. Additionally, cases with incomplete demographic information were excluded from inferential analyses (though they were retained in descriptive statistics when feasible). These steps ensured that the analytic sample was complete for all variables of interest.

Data Analysis: Data were analyzed using a multi-step quantitative strategy to address the research questions. First, I computed descriptive statistics to summarize the central tendency and dispersion of age, ethnicity, and exam scores in the sample. Next, I conducted one-way analyses of variance (ANOVAs) to test for mean differences in academic performance by age group (traditional-age vs. non-traditional) and by ethnic group separately. I then used a two-way ANOVA to examine the interaction effect of age and ethnicity on exam scores. All ANOVA assumptions (normality, homogeneity of variance, and independence) were checked and met before running these tests. Where the ANOVAs indicated significant differences between groups, I followed up with Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) post-hoc tests to determine which specific groups differed significantly from each other.

In addition to the ANOVAs, I employed multiple linear regression analysis to further probe the joint influence of age and ethnicity on academic performance. The regression models included main effects for age and ethnicity as well as an age × ethnicity interaction term, allowing me to assess whether the combination of age and ethnic identity had an effect on exam scores beyond their individual contributions. Age was entered as a continuous predictor in one set of models and as a categorical predictor (using the traditional vs. non-traditional classification) in an alternate set, to ensure robustness of the findings. For models treating age as a continuous variable, I mean-centered the age variable prior to creating the interaction term to minimize multicollinearity (Aiken & West, 1991); examination of variance inflation factors confirmed that multicollinearity was not a concern. I evaluated overall model fit using R² and adjusted R² values and examined F-statistics for model significance. The significance of individual regression coefficients was assessed with t-tests, using p < .05 as the threshold for statistical significance (with p < .01 and p < .001 indicating more stringent levels of significance, and noting p < .10 as a marginal trend).

All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics (Version 28), and key results were cross-validated using R software to ensure accuracy. Missing data were handled with listwise deletion in inferential analyses, since fewer than 5% of cases had any missing values. Little’s MCAR test indicated that the missing data were Missing Completely At Random, suggesting that excluding those few cases had not introduced systematic bias. Finally, to check the robustness of my findings, I ran supplementary analyses including prior GPA as a covariate in the ANOVA and regression models. These robustness checks yielded substantively similar results, indicating that the observed age and ethnicity effects were not driven by pre-existing differences in students’ academic preparedness.

Table 1 presented the descriptive statistics for the key study variables. The overall mean average exam score was 14.46 (SD = 2.72) out of a maximum of 20 points. Traditional-age students (ages 18-24) had a mean exam score of 14.20 (SD = 2.65), while non-traditional students (ages 25 and older) had a higher mean of 15.32 (SD = 2.71). In terms of ethnicity, Asian and White students demonstrated higher average exam scores (M = 15.12 and 14.98, respectively) compared to Hispanic/Latino (M = 13.74) and African American students (M = 13.38). Students categorized as “Other” had a mean score of 14.15.

| Variable | n | M | SD |

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall Sample | 384 | 14.46 | 2.72 |

| Traditional-Age (18–24) | 284 | 14.20 | 2.65 |

| Non-Traditional (25+) | 100 | 15.32 | 2.71 |

| Asian Students | 123 | 15.12 | 2.48 |

| White Students | 115 | 14.98 | 2.53 |

| Hispanic/Latino Students | 100 | 13.74 | 2.83 |

| African American Students | 23 | 13.38 | 2.90 |

| Other Ethnicity | 23 | 14.15 | 2.71 |

Age and Academic Performance: A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine differences in exam performance based on age group (traditional vs. non-traditional students). The results indicated a statistically significant difference in average exam scores between the two age groups, F(1, 382) = 9.57, p = .002, η2 = .024. Non-traditional students outperformed traditional-age students, with a mean difference of 1.12 points on the 20-point exam scale.

Post-hoc analyses were not necessary for age, given the binary grouping. However, the effect size (η2 = .024) suggested a small-to-moderate practical significance according to Cohen’s (1988) guidelines.

Ethnicity and Academic Performance: A separate one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine differences in exam scores across ethnic groups (Asian, White, Hispanic/Latino, African American, Other). The results revealed a statistically significant effect of ethnicity on exam scores, F(4, 379) = 6.14, p < .001, η2 = .061.

Post-hoc Tukey’s HSD tests indicated that Asian students scored significantly higher than Hispanic/Latino students (mean difference = 1.38, p < .001) and African American students (mean difference = 1.74, p = .002). White students also outperformed Hispanic/Latino students (mean difference = 1.24, p = .003) and African American students (mean difference = 1.60, p = .007). No significant differences were found between Asian and White students or between Hispanic/Latino and African American students. These findings suggested meaningful ethnic differences in academic outcomes within the quantitative course examined.

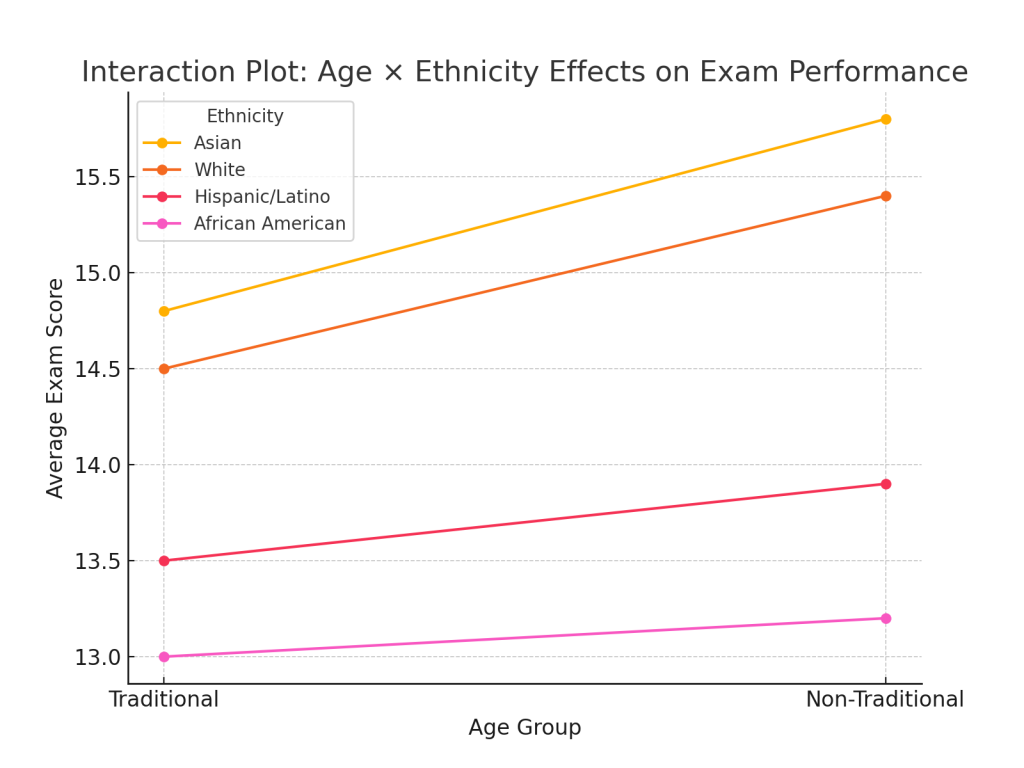

Two-Way ANOVA: Age and Ethnicity Interaction: To explore whether age and ethnicity interacted to influence exam performance, a two-way ANOVA was conducted with age group and ethnicity as factors. The analysis revealed significant main effects of age (F(1, 374) = 7.90, p = .005, η2 = .021) and ethnicity (F(4, 374) = 5.72, p < .001, η2 = .058). An age × ethnicity interaction effect was also observed (F(4, 374) = 2.11, p = .078, η2 = .022). Although this interaction did not reach the conventional significance threshold (p < .05), the trend suggested that the performance advantage associated with older age varied across ethnic groups. Specifically, older Asian and White students demonstrated stronger performance gains relative to their younger counterparts, whereas the age-related advantage was less pronounced among Hispanic/Latino and African American students. Figure 1 visually illustrates these interaction patterns.

Main Effects Model: A multiple regression analysis was conducted to further examine the predictive value of age, ethnicity, and their interaction on academic performance. In the initial model, age (continuous, in years) and ethnicity (dummy-coded with White as the reference group) were entered as predictors.

The overall model was significant (R2 = .117, F(5, 378) = 9.99, p < .001). Age positively predicted exam scores (β = 0.15, p = .002). Additionally, being Hispanic/Latino (β = -0.18, p = .004) or African American (β = -0.20, p = .008) predicted significantly lower exam scores compared to White students. No significant differences were found for Asian or “Other” ethnicities relative to White students after controlling for age.

Interaction Effects Model: In the second model, age × ethnicity interaction terms were added to test whether the relationship between age and performance differed by ethnic group. The model explained a slightly greater proportion of variance (R2 = .132, F(9, 374) = 6.56, p < .001). This model revealed a significant positive interaction between age and Asian ethnicity (β = 0.11, p = .041), indicating that older Asian students benefited more from age-related academic advantages. It also showed a marginal negative interaction between age and African American ethnicity (β = -0.09, p = .092), suggesting that older African American students did not experience the same degree of performance boost with increasing age. All variance inflation factors (VIFs) were below 2.5, indicating no serious multicollinearity issues. Regression coefficients are summarized in Table 2.

| Predictor | B | SE B | β | t | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 14.87 | 0.32 | – | 46.47 | <.001 |

| Age (continuous) | 0.03 | 0.01 | 0.15 | 3.14 | .002 |

| Asian (vs. White) | 0.14 | 0.28 | 0.02 | 0.50 | .618 |

| Hispanic/Latino (vs. White) | -0.88 | 0.30 | -0.18 | -2.93 | .004 |

| African American (vs. White) | -1.05 | 0.39 | -0.20 | -2.70 | .008 |

| Other Ethnicity (vs. White) | -0.45 | 0.37 | -0.07 | -1.22 | .223 |

| Age × Asian | 0.06 | 0.03 | 0.11 | 2.05 | .041 |

| Age × Hispanic/Latino | -0.03 | 0.03 | -0.06 | -0.92 | .357 |

| Age × African American | -0.08 | 0.05 | -0.09 | -1.69 | .092 |

| Age × Other Ethnicity | -0.02 | 0.05 | -0.02 | -0.43 | .667 |

Note. White students and mean-centered age served as reference categories. R2 = .132, Adjusted R2 = .111, p < .001.

Overall, older (non-traditional) students achieved higher course performance than traditional-age peers. Ethnic disparities were also present, with Asian and White students outperforming Hispanic/Latino and African American students on average. Importantly, the magnitude of the age advantage varied across ethnic groups—being stronger in some and attenuated for others (notably for African American students)—indicating that the benefits typically associated with age and life experience did not accrue uniformly.

The patterns observed suggested a complex interplay between demographic factors and academic performance, underscoring the need for differentiated academic supports based on both age and ethnic background.

Interaction Plot Interpretation: To further illuminate the interaction between age and ethnicity on academic performance, an interaction plot (Figure 1) was generated. The plot revealed that for Asian and White students, average exam scores increased noticeably with age. Among Asian students, non-traditional-age individuals (25 years and older) achieved notably higher mean exam scores compared to their traditional-age counterparts, with a steeper slope indicating a stronger positive relationship between age and performance. A similar but slightly less pronounced pattern was observed for White students.

In contrast, Hispanic/Latino and African American students displayed flatter slopes in the interaction plot. While non-traditional Hispanic/Latino students slightly outperformed their traditional-age counterparts, the magnitude of the difference was modest. For African American students, the slope was almost flat, suggesting that age conferred little to no academic advantage in this subgroup. Students classified as “Other ethnicity” showed a trend intermediate between the Asian/White and Hispanic/Latino/African American patterns, although the small sample size warrants caution in interpretation.

These visual patterns reinforced the regression findings, where a significant positive interaction between age and Asian ethnicity, and a marginally negative interaction between age and African American ethnicity, were observed. The data suggested that while older age generally supports higher academic performance, the strength and nature of this advantage are not uniformly experienced across all ethnic groups. Particularly, cultural, institutional, and systemic factors may moderate the extent to which resilience associated with older age translates into academic success among diverse student populations.

Robustness Checks: To ensure that the observed results were not artifacts of prior academic preparation, robustness checks were conducted using cumulative GPA at the start of the semester as a covariate. Including GPA in the models slightly reduced the magnitude of the age and ethnicity effects but did not eliminate them. The age advantage for non-traditional students remained statistically significant (p = .006), and ethnic disparities persisted, particularly for Hispanic/Latino and African American students compared to White students. The interaction between age and Asian ethnicity also remained significant (p = .038) after controlling for GPA.

Additionally, alternative model specifications treating age as a categorical variable (traditional vs. non-traditional) rather than continuous yielded substantively similar results, bolstering confidence in the robustness of the findings. No significant multicollinearity issues were detected across any model iterations.

Overall, these robustness checks suggested that the identified patterns are stable and not merely reflections of pre-existing academic performance differences, further supporting the study’s core findings regarding the complex interplay of age, ethnicity, and academic outcomes in higher education.

Findings from this study provide important insights for equity-oriented teaching and institutional practice in higher education. Consistent with prior research, both age and ethnicity shaped how students navigated quantitatively intensive gateway courses (Bye, Pushkar, & Conway, 2007; Museus & Quaye, 2009). The performance advantages observed for non-traditional-age students align with evidence that older learners often display stronger academic resilience, self-regulation, and persistence (Kasworm, 2010). At the same time, the significant ethnic disparities documented here mirror broader patterns of racialized inequity in quantitative and STEM-related fields (Chen, 2013; Lubienski, 2002; Steele & Aronson, 1995). Importantly, the interaction between age and ethnicity underscores calls from intersectionality scholars for analyses that consider how multiple social identities intersect to shape educational opportunity structures (Crenshaw, 1991; Posselt & Grodsky, 2023). Together, these findings emphasized the need for institutional approaches that recognize the complex, layered dynamics of age, race, and lived experience in shaping student achievement.

One major implication of this study is the need for institutions to design differentiated academic support systems that account for the distinct needs of traditional-age and non-traditional-age students. Research consistently shows that older learners bring strengths such as self-regulation, persistence, and goal-oriented behavior, yet they often face substantial external demands—including employment and caregiving responsibilities—that shape how they engage with coursework (Kasworm, 2010; Donaldson & Townsend, 2007 ; Rabourn, BrckaLorenz, & Shoup, 2018). Flexible instructional supports, extended tutoring availability, and hybrid or online learning options have been shown to meaningfully benefit adult learners managing complex life commitments (Chen, 2013; Tinto, 2012). Conversely, younger students frequently require stronger foundational scaffolding, structured study guidance, and intentional community-building to support academic integration and persistence (Tinto, 2012; Crisp et al., 2017). By acknowledging these divergent needs, institutions can implement support structures that are both age-responsive and equity-oriented, reducing barriers that disproportionately affect students at different life stages.

The ethnic performance patterns observed in this study underscored the critical role of culturally responsive and anti-deficit pedagogy in quantitatively intensive courses. Scholars have long argued that students’ academic engagement and achievement improve when instructional practices affirm their cultural identities, values, and ways of knowing (Ladson-Billings, 1995; Gay, 2018). In quantitative disciplines, where deficit narratives and stereotypes are especially pervasive, culturally responsive teaching could disrupt racialized patterns of underperformance by reframing mathematical and statistical reasoning as accessible, learnable competencies rather than fixed traits (Nasir et al., 2008). Moreover, students from minoritized backgrounds often navigate stereotype threat and belonging uncertainty, both of which have demonstrated negative effects on performance in STEM contexts (Steele & Aronson, 1995; Walton & Cohen, 2007). Evidence-based interventions—such as values-affirmation activities, growth mindset framing, and inclusive course design—have been shown to narrow performance gaps and strengthen persistence among underrepresented students (Miyake et al., 2010; Cohen et al., 2006). An explicitly anti-deficit orientation, aligned with frameworks like Community Cultural Wealth, positions students’ lived experiences as assets rather than shortcomings and challenges institutions to transform classroom norms and expectations (Yosso, 2005; Solórzano & Yosso, 2002). Collectively, this literature affirms that culturally responsive pedagogy is central to equitable learning environments, particularly in quantitative gateway courses where racialized performance disparities persist.

The findings also highlight the importance of mentorship, community building, and advising structures that are responsive to students’ intersecting identities. Prior research demonstrated that meaningful mentoring relationships—both peer and faculty—significantly enhance students’ sense of belonging, academic engagement, and persistence, particularly for students from racially minoritized backgrounds (Crisp et al., 2017; Salas et al., 2014). Non-traditional-age students may benefit from individualized advising and flexible degree pathways that acknowledge their work, family, and financial responsibilities, which have been shown to shape adult learners’ academic trajectories (Donaldson & Townsend, 2007; Kasworm, 2010). Younger students, by contrast, often require structured opportunities to form academic communities and develop college navigation skills, as social integration remains a key predictor of persistence in early undergraduate years (Tinto, 2012; Museus & Quaye, 2009).

Culturally informed advising models—grounded in frameworks such as Community Cultural Wealth—can help students draw on their aspirational, familial, and navigational forms of capital to persist in demanding academic environments (Yosso, 2005; Solórzano & Yosso, 2002). Research further indicates that mentoring programs that pair students with mentors who share similar cultural backgrounds or educational trajectories can strengthen identity development and foster greater academic self-efficacy (Hurtado et al., 1998; Crisp et al., 2017). In quantitative gateway courses, where performance disparities are often magnified, such relational support structures can play a crucial role in counteracting stereotype threat, building confidence, and sustaining persistence. Accordingly, targeted mentorship and advising initiatives represent a critical component of an institutional strategy to address inequities at the intersection of age and ethnicity.

The study’s findings also carry important implications for diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) policy and institutional research practices. Although age diversity has expanded considerably in higher education, institutional DEI frameworks often prioritize race and ethnicity while overlooking how age interacts with these identities to shape student outcomes (Ryu, 2010; Lumina Foundation, 2022). Yet research increasingly demonstrates that demographic categories do not operate in isolation; instead, educational inequities emerge from the interaction of structural forces tied to race, socioeconomic status, age, and other dimensions of identity (Harper, 2012; Posselt & Grodsky, 2023). The performance patterns in this study—particularly the differential academic benefits associated with older age across ethnic groups—underscore the importance of adopting intersectional approaches when crafting DEI strategies and evaluating institutional effectiveness.

Institutional research offices can play a central role by routinely disaggregating academic performance data by multiple demographic dimensions, including age within racial/ethnic groups to illuminate hidden patterns of inequity (Bensimon, 2007). Such practices align with emerging recommendations for more nuanced metrics of student success that move beyond aggregate statistics to illuminate hidden patterns of inequity (Posselt & Grodsky, 2023; Bensimon, 2007). Additionally, DEI policy initiatives should explicitly acknowledge the needs of non-traditional students, who often navigate financial strain, complex family obligations, and limited institutional support despite representing a growing proportion of the student population (Choy, 2002; Kasworm, 2010). Expanding scholarships, emergency funding, and support programs specifically for adult learners—particularly adult learners of color—can help mitigate structural barriers that disproportionately affect these groups (Goldrick-Rab & Sorensen, 2010).

Finally, climate assessments and institutional equity audits should incorporate questions related to age diversity, family responsibilities, and perceptions of inclusion for adult learners. Prior research has shown that institutional norms and campus cultures strongly influence students’ sense of belonging and persistence, especially for students from marginalized backgrounds (Hurtado et al., 1998; Museus & Quaye, 2009). Integrating these considerations into DEI policy provides a more comprehensive foundation for addressing inequities in quantitatively intensive gateway courses and across the broader academic environment.

Finally, the study’s findings highlight the importance of cultivating campus cultures that meaningfully recognize and celebrate both age and cultural diversity. Students’ perceptions of institutional climate—including whether they feel visible, valued, and supported—were shown to influence academic engagement, persistence, and well-being (Hurtado et al., 1998; Strayhorn, 2019). For adult learners and students of color, campus environments that privilege traditional-age norms or implicitly center whiteness can exacerbate feelings of marginalization and reduce their sense of belonging (Harper & Simmons, 2019; Museus & Quaye, 2009). Given the intersectional patterns identified in this study, efforts to strengthen campus climate must attend to the ways age, race, and lived experience interact to shape students’ daily navigation of the institution.

Inclusive messaging, representation in marketing materials, and institutional narratives that affirm non-linear educational pathways were found to support belonging among diverse student populations (Hurtado et al., 1998; Vaccaro & Newman, 2016). Likewise, adult learners often report greater integration when institutions recognize their prior experiences, provide designated spaces or communities, and offer programming that aligns with their schedules and responsibilities (Association of American Colleges & Universities, 2022; Kasworm, 2010). For students of color, culturally relevant programming, racial/ethnic affinity groups, and visible commitments to anti-racism contribute to stronger identity development and academic confidence (Ladson-Billings, 1995; Gay, 2018). When campuses adopt an inclusive excellence model—one that embeds equity into academic, social, and cultural practices—students across demographic groups are better positioned to thrive.

In this context, the present findings affirm that performance disparities in a quantitative gateway course reflect not only instructional or curricular factors, but also broader structural and cultural conditions. Building an inclusive campus culture therefore represents a necessary complement to course-level interventions, ensuring that the strengths of older learners and racially minoritized students are recognized and supported within the institution’s everyday practices.

This study was not without limitations. First, it was conducted at a single institution, which might have limited the generalizability of findings to other types of colleges or universities, especially those with different demographic compositions or institutional structures. Second, although the sample size allowed for robust statistical modeling, some subgroups—such as older Hispanic/Latino and African American students—were relatively small, which introduced the potential for statistical noise and limited the precision of those subgroup estimates. Third, the study used a cross-sectional design based on institutional records, which precluded any claims about causality or changes over time. Fourth, reliance on institutional data, while valuable for large-scale analysis, did not provide insight into students’ lived experiences, motivations, or perceptions of challenge and support. It also did not capture potentially relevant unmeasured variables, such as employment hours, caregiving responsibilities, or prior educational background, that could have influenced academic performance. Future research should incorporate longitudinal data and mixed-methods designs that include interviews, focus groups, or surveys to better capture students’ intersectional realities and to deepen understanding of how age and ethnicity interact with academic experiences.

Equally important are the implications for practice and pedagogy in higher education. The findings call for culturally responsive and age-inclusive teaching strategies that acknowledge the diverse assets and challenges of different student groups. In practical terms, institutions might consider targeted interventions —for example, mentoring programs, curriculum adjustments, or tailored support services— for older students from underrepresented ethnic backgrounds, to ensure the wealth of experience these learners bring is recognized and translated into academic success. Ultimately, by centering structural equity and embracing an intersectional approach, this research moved beyond gap-gazing to illuminate the root causes of achievement disparities. In doing so, it provides a roadmap for educators and policymakers to actively dismantle the structural barriers that impede student success, helping colleges and universities fulfill their commitments to inclusive excellence.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

ISSN: 2998-8470