| Beatriz Desantiago-Fjelstad, EdD* | |

| Bernadeia H. Johnson, EdD* | All from the Department of Educational Leadership, Minnesota State University, Mankato |

| Melissa Krull, PhD* | |

| Joel Leer, PhD* |

We* have no known conflict of interest to disclose.

Educational leadership faculty from a predominantly White midwestern university sought to improve the learning experience for graduate students of color. Racial affinity groups were introduced as an instructional method. Students in several graduate courses participated in racial affinity groups for one semester. Survey results showed psychological and physiological benefits of processing and discussing content through racial affinity. Using racial affinity groups as an instructional practice in graduate courses can lead to less fatigue among students of color.

Keywords: Culturally Relevant Education, Fatigue, Microaggressions, Race

If you look into any higher education classroom, particularly a graduate school classroom, you will see that they have become multiracial learning spaces. In fact, like many urban public school districts across the United States of America, minority students have become the majority–nearly 65%–of enrollees in post-baccalaureate programs (NCES, 2021). However, the racial makeup of university faculty remains nearly 75% white (NCES, 2020). These realities require graduate school faculty to embrace a race-conscious approach to instruction and facilitation.

So that’s what we did. Our team of graduate faculty at a predominantly White midwestern university began to refine our efforts to utilize race-conscious instruction. We employed racial affinity groups in several graduate courses during the fall semester of 2022 to help students of color avoid the fatiguing effects of racial isolation and microaggressions. Through their racial lenses, students could offer views, perspectives, and ideas to others with similar racial experiences. Students of color were then surveyed about the effects of these affinity groups using William Smith’s (2006) racial battle fatigue framework. Specific questions related to psychological, physiological, and emotional/behavioral stress were embedded in the survey questions to elicit perspectives on the impact of racial affinity on racial battle fatigue.

University programs are typically grounded in White standards, practices, and instructional approaches. While White students can discuss and relate to other White peers in White-dominated learning spaces regularly, students of color lack that opportunity. As a result, they can be negatively impacted academically by issues such as language barriers, systemic discrimination, and lack of representation when their cultural backgrounds are not thoughtfully considered (Kelly, 2019). Race-conscious instruction and facilitation require university faculty to acknowledge these potential barriers, respond to them with inclusive course content design, and mitigate them in ways that give students of color the same access and opportunity afforded white students. Understanding and responding to race, culture, places of origin, and trauma-related issues among graduate students of color can inform graduate classroom instruction and enhance student learning.

Culturally relevant teaching resources, advising strategies, and instructional pedagogy can also advance the learning experience. An example of race-conscious facilitation and culturally relevant instructional pedagogy that was applied in our graduate coursework was inspired by an African American male student who abruptly asked, “Why are we always teaching White people how to be leaders and not Black people?” This question shocked the class, revealing the discomfort among White students and prompting cautious nods from peers of color. Instead of dismissing the interruption, a Black faculty member leading the course recognized the need to address the issue immediately and split the class into two breakout rooms: one for White students and one for students of color, allowing them to choose. Students were instructed to reflect on their feelings related to the in-class emotional race-based remarks using Singleton’s Courageous Conversation Protocol (Singleton, 2015) and to share their positions using the Compass. In both rooms, the instructor shared her identity as an African American female educator and emphasized her commitment to honoring the diversity of future students in the environments where they will lead. Students of color discussed the heavy burden they and others often carry and the need for White colleagues to share this responsibility of understanding diverse communities. Students reconvened as a full group and highlighted the importance of processing issues related to racial identity in racial affinity groups. In the White breakout room, a White female student acknowledged the importance of giving space to classmates of color but emphasized that White students need to learn from their peers of color. The instructor stressed the need for White leaders to take responsibility for their education and advocacy, rather than relying solely on their peers of color, underscoring the crucial need for White students to understand and support their diverse classmates.

Race-conscious instruction can also minimize the steady and lasting adverse effects of alienation, isolation, and racism from White students and faculty toward students of color at predominantly White institutions (Matthews, 2017). Without race-conscious instruction, first-generation, Black, Indigenous, and other underrepresented students in predominantly White academic spaces face steep learning curves while also experiencing a negative impact on their social well-being. Additionally, the lack of racial representation among professors and peers compounds their challenges even in those situations in which white faculty are practicing race-conscious instruction (Gunaratne & Lumb, 2023).

In contrast, learning spaces that are White-dominated and where race consciousness is absent create conditions for intentional or unintentional racial microaggressions to emerge. These aggressions communicate hostility to the receiver and create psychological dilemmas for both the White perpetrators and the students of color (Sue et al., 2007). Ultimately, these steady aggressions become one of many forms of racial battle fatigue (Smith 2008). Further, students of color who constantly aim for a status in academic settings that don’t regard race often face frustration and despair when it proves unattainable (Bell, 1992). Feeling understood as a learner is essential to the learning process, and access to an equitable and empowering education for all students is critical to our national well-being (Darling-Hammond, 2010). Eliminating the fatigue of racial isolation can improve the graduate learning experience for students of color.

In a conversation with a colleague who was researching racial battle fatigue and racial microaggressions, this same Black faculty member shared her earlier classroom experiences. This prompted her to reflect on the research related to microaggressions and racial battle fatigue, including her own lived experiences. A year after the student’s outburst in class, the incident was still having an impact on her. Ultimately, that outburst encouraged her to rethink her teaching methods creating a more racially authentic learning experience among classmates through the use of the affinity group process. Race-conscious instruction, or the lack thereof, is at the heart of the challenge of making graduate classrooms more productive learning spaces for students of color.

This singular instance led to discussions among the department faculty about how to consistently and intentionally confront the challenge of making graduate classrooms more productive learning spaces for students of color. Regular use of affinity groups was a big part of that shift. Our findings: alternating away from mixed-racial learning spaces minimized uncertainty, feelings of isolation, and even the idea that they are “an only” and, therefore, not understood. For students of color, affinity spaces proved to validate them and allowed them to discuss content without pressure or judgment from those in the dominant White culture.

Race-conscious instruction requires university faculty to understand microaggressions and racial battle fatigue. Racial battle fatigue is the “cumulative result of a natural race-related stress response to distressing mental and emotional conditions. These conditions emerge from constantly facing racially dismissive, demeaning, insensitive, and/or hostile racial environments and individuals” (Smith, p. 615–618). Steady racist microaggressions lead to long-term fatiguing stress responses for students and educators of color (Smith, 2008). As a result, racial battle fatigue sets in, creating stress responses that, over time, take an exhaustive toll on people of color physiologically, psychologically, and emotionally.

Racial microaggressions are the everyday overt and covert raced-based insults that negatively impact the lives of people of color. They deliver denigrating messages to people of color that are focused on their membership in a racial minority group. They are subtle but often stunning, often automatic, and frequently non-verbal (Sue, 2007; Pierce, 1970). Microaggressions can also emerge in ways that are unconscious to the offender. Even subtle facial expressions or voice tones can be intrusive, especially if that tone or expression is received negatively in some way. Unfortunately, the tendency to overlook or ignore the subtleties of these seemingly innocuous behaviors is common among both the offender and the receiver. Responding to and eliminating microaggressions, then, means we must be alert to not only the grotesque and obvious–what we think of as racial slurs, but also the subtle, cumulative mini-assaults that are more at the center of today’s racism (Pierce, 1974). The confluence of racial battle fatigue and microaggressions is the place where these separate impactful slights compile over time and collectively render the recipient exhausted and unable to counter the chronic nature of the racial offenses. Faculty members of color offer their own testimonies and lived experiences with microaggressions and racial battle fatigue as impetus for this research. As one Black female faculty member recalls:

I have endured and witnessed another type of microinsult while in my university position that reveals the often unconscious yet hostile words and behavior people of color perceive as a questioning of their intelligence, credentials, and worthiness to be in the room. I was naive in thinking that working in a university setting would mean interacting with graduate students who possess a certain level of maturity and acceptance of difference. During one of my classes, I started to introduce myself and was quickly interrupted by a 6’2” White male student who told me he knew all about me because he did an investigation on me. He went on to explain his reasoning, he was a former police officer and wanted to know who was going to teach his class. I was taken aback and tried to hide my shock as I decided, as I have done a million times, to enter into a quick session of self-talk . . . of course, he used his special skills and abilities to `get to know you’ . . . /B.S.} He then pulled out a file folder and handed it to me with pride to show me the materials he had collected on me. I was shocked and kept this information to myself. I asked other White faculty who had this student in their classes if they were given a research file on themselves, and the answer was no. This example was just one of many experiences that, while one White man’s actions were seemingly innocent, were not only aggressive to me but offensive and yes, emotionally exhausting.

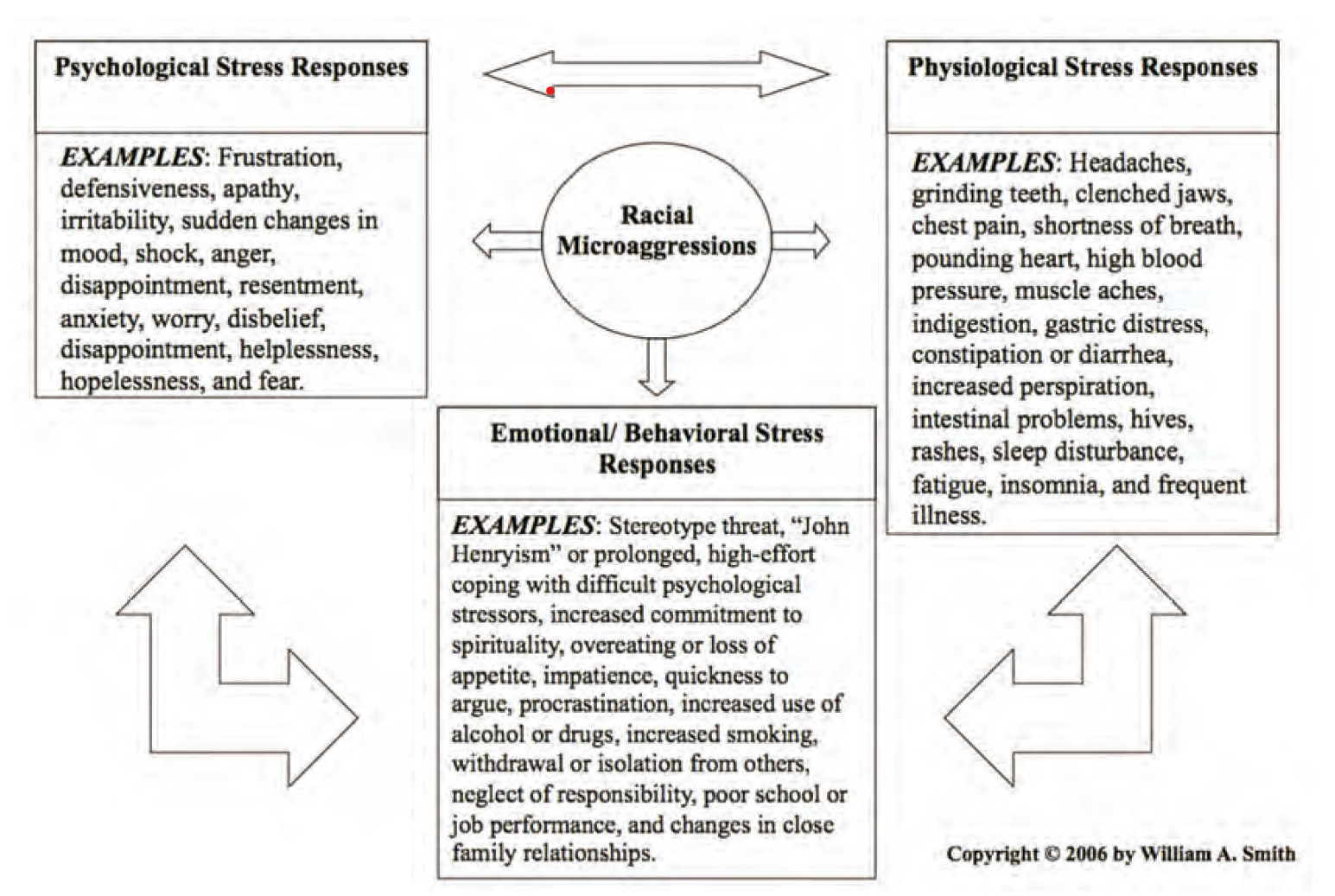

Smith’s theoretical construct (2006, as cited in Smith, Hung, & Franklin, 2011a) illustrates the causality between racial fatigue and microaggressions (See Figure 1). The interdisciplinary theoretical framework defines the various levels and interconnectedness of psychological, physiological, and behavioral stress responses. For example, fatigue resulting from microaggressions manifests through (a) psychological stress responses such as fear, hopelessness, resentment, or even anxiety; (b) physiological stress responses such as headaches, high blood pressure, or insomnia; or (c) emotional/behavioral stress responses such as procrastination, a quickness to argue, or impatience.

While the above three stress response categories are important, psychological stress responses to racial battle fatigue appear most prominent within the research. For example, Smith et al. (2011b) found in their study of the miseducation of Black males that depression, tension, and rage were the most prevalent results of microaggressions. This dynamic between racial microaggressions and the resulting racial battle fatigue points to both personal and professional interference for people of color.

The effects of this combination are also detrimental when examining the lived experiences of Black school principals (Krull & Robicheau, 2020), who reported that microaggressions and racial battle fatigue were steady and consistent. They reported experiencing psychological stress responses such as disbelief, disappointment, frustration, and defensiveness. Physiologically, they reported fatigue, sleep disturbance, a pounding heart, and headaches. Additionally, these same leaders reported lingering stress responses of isolation and sleeplessness while also striving to lead schools. Research on college campus culture (Smith et al., 2016) found similar racial battle fatigue patterns for Black students who reported feelings of dehumanization, alienation, anger, and frustration due to microaggressions and racial battle fatigue.

Providing support, acknowledgment, safety, and belonging for all students, especially students of color, will help faculty avoid, minimize, or even eliminate the experiences that result in racial battle fatigue. Learning will be much more efficient and effective if racial stress is not present. While many culturally relevant instructional strategies can facilitate effective learning for all graduate students, racial affinity grouping strategies can lead to a safer, more stress-free experience, especially for students of color.

In educational settings with higher retention rates among educators of color or where educators of color have made inroads with equity initiatives, affinity groups have been critical for support, learning, and healing. Educators of color need racial affinity spaces to support their political, pedagogical, and relational growth (Pour-Khorshid, 2018). Otherwise, racial battle fatigue can quickly set in as students of color face daily interpersonal, pedagogical, and structural obstacles. With racial affinity groups, students can feel empowered to persist through a graduate program from which they would otherwise strongly consider disenrolling (Bennett, 2000). Similarly, racial affinity groups not only helped students of color learn the subject matter more effectively but also helped them understand who they are and how beneficial it can be for students of color to support one another as they cope academically and socially in a white-dominated environment like post-baccalaureate programs (Aguilar & Gross, 1999). Racial affinity groups are where issues can surface, communication skills can improve, and students can develop a sense of pride and belonging in their school. Through their formation, the schools demonstrate that they recognize and value all students (Aguilar & Gross, 1999).

These kinds of outcomes were evident in our own experiences with racial affinity groups as one of our graduate students of color shared that they value the racial affinity group in class because it provides space to connect and be authentic with peers of color. In their largely White workplace, they felt the constant pressure to represent Black students, connect with Black families to talk about academic and behavioral issues, respond to student behavior issues, and serve on the equity team, which forced them to routinely be known as the “go-to” person. In racial affinity group activities, they felt relieved of the burden of being the spokesperson for their race and therefore could engage in discussions without having to justify or explain to White colleagues.

Racial affinity group members express gratitude for simply having access to a learning space where they can regularly engage with other educators of color. Their shared commitment to resisting White supremacy allowed members to experience deeper learning that was impossible within their respective school sites (Pour-Khorshid, 2018). To wit, one student in our program explained:

There’s definitely a sense of camaraderie that I cling to in [the racial affinity group], being able to build with folks whom you see eye to eye with, where you can start on page two and not have to constantly explain yourself or define or defend shit.

Opportunities for Black students to be together allow them to talk about issues that hinder their performance—things like overt racism, isolation, academic anxiety, homework dilemmas, and psychological safety (Tatum, 1997). Students describe how these affinity groups allow them to support, look out for, and even help one another with their academic work. And significantly, they are cognizant of the innate challenges of succeeding as students of color in predominantly white classrooms (Tatum, 1997). Students of color become more active and involved in course content when they engage in affinity groups. They learn to lean on each other, and when they do, they learn at a much higher and more profound level (Kelley et al., 2019).

The intentional grouping of students of color allows them to share common experiences and flourish. It has also allowed them to explore and celebrate their differences more thoroughly. Indeed, one educator of color described it this way:

What’s really beautiful about [the affinity group] is that because we’re explicitly a [people of color] group, the ways in which we are all very different show up when we’re together, and we reflect much deeper about our identities and about how the varying experiences in our space shape what it means to teach our student population as who we are (Pour-Khorshid, 2018, p. 323).

Another educator of color shared that the affinity group was:

One of the few places in my life where I can be fully myself. We’re constantly bombarded with talk about intersectionality, but it’s incredibly rare to actually feel what it’s like to be in a community that deeply embraces my complexity so that I don’t have to constantly be explaining away one aspect of my experience like the struggle of being a teacher of color (Pour-Khorshid, 2018, p. 324).

However, it is important to note that affinity groups need to be more than simply a place for people with commonalities to come together (Jackson 2011). Rather, they are intended to create an environment that allows racial groups to maximize their learning and promote their academic strengths. It was in this spirit that affinity groups were utilized in our specialist program—recognizing that racial battle fatigue and microaggressions could only be confronted and mitigated if we provided consistent specific opportunities for students of color to reflect and interact free of those inhibiting factors. In our courses, we provided a supportive space for our students to engage in meaningful discussions about race and personal experiences. The affinity groups allowed our students of color to discuss their experiences and share strategies for racial issues without explaining or justifying their experiences to white peers. The affinity groups helped participants process their experiences in a safe environment and led to enriching discussions on equity and inclusion.

While White students likely rarely internalize the value of being in the company of people of their race most of the time–simply because it happens so frequently, the value of interacting consistently with people who look like them and have their shared experience is profound (McIntosh, 1988). So, too, the ten students of color who provided survey feedback about the effects of these affinity groups provided poignant insight into how impactful these racial affinity groups were, both psychologically and physiologically. Their responses illuminated how microaggressions and racial battle fatigue have impacted their educational and professional journey up to this point and the wide range of ways racial affinity groups increased their learning and improved their licensure program experience. One student indicated they were, “able to share my thoughts unabridged with an unspoken understanding within my affinity group rather than choosing not to share or sharing and having to explain in mixed company.”

Regarding psychological stress, 80% of the participants indicated they always experienced less anger in affinity groups than in mixed-race groups. Similarly, two-thirds of participants indicated they have fewer sudden changes in mood, less frustration, and less irritability when allowed to discuss curricular topics with only students of their race. Furthermore, 70% indicated they always experienced less worry and anxiety in affinity groups. One student captured this decrease in anxiety and frustration in a poignant fashion:

I didn’t have as much anxiety about presenting or sharing my experiences. I didn’t have to pre-think what my responses would be and I had to explain myself less often. I also built stronger relationships with my classmates of color. I was less frustrated because I didn’t encounter ignorant remarks or feel like I was there for someone else’s learning.

While experts across the educational research spectrum have discussed the importance of social and emotional health among children, these numbers prove that it’s also essential for adult learners. Furthermore, Dr. Yvette Jackson’s research on the effects of culturally relevant instruction and the resulting shifts in confidence and brain activity applies to young learners and learners of all ages (Y. Jackson, personal communication, February 28, 2023).

It would be hard to assert that resentment, helplessness, apathy, disappointment, and defensiveness do not negatively affect one’s learning. It is equally poignant that half of the participants always felt less helplessness, disappointment, apathy, and defensiveness when allowed the opportunity to work in affinity groups, and 70% felt less resentment. It is worth emphasizing that these participants are veteran educators and motivated adult professional learners significantly impacted by the affinity experience.

Equally telling are the responses from our students who spoke to the positive physiological impact of affinity groups on graduate students of color. For example, over half of participants said that having affinity groups consistently in their courses helped them sleep better, reduced stomach discomfort and muscle aches, allowed them to breathe more freely, and even caused them to clench their jaws and grind their teeth less often. While this list reads like the results of a medical trial, it is simply the realized impacts students of color encountered when allowed to be in classroom affinity groups. Also worth noting was that 76% of participants noticed affinity groups reduced their heart pounding, and two-thirds acknowledged that they experienced less fatigue, less frequent chest pains, and fewer headaches.

Equally telling are the responses from our students who spoke to the positive physiological impact of affinity groups on graduate students of color. For example, over half of participants said that having affinity groups consistently in their courses helped them sleep better, reduced stomach discomfort and muscle aches, allowed them to breathe more freely, and even caused them to clench their jaws and grind their teeth less often. While this list reads like the results of a medical trial, it is simply the realized impacts students of color encountered when allowed to be in classroom affinity groups. Also worth noting was that 76% of participants noticed affinity groups reduced their heart pounding, and two-thirds acknowledged that they experienced less fatigue, less frequent chest pains, and fewer headaches.

The power of these numbers lies in their invisibility. While students of color may be showing some of these emotional and physical responses to their professors and classmates, more than likely, these responses are invisible to White students around them. As one participant described it, “I have witnessed and experienced that a bifurcation occurs within us. We leave a part of ourselves outside the schoolhouse to either survive or navigate Whiteness.”

Our graduate program aims to maximize learning experiences and optimize the program’s impact. With that goal in mind, creating the opportunity for students of color to share their thoughts unabridged, with an unspoken understanding within an affinity group, is a big step toward that goal.

Our leading role as university educators has and always should be providing the avenues necessary for students to maximize their content learning and development as future school leaders. Affinity groups have helped students of color do just that as one graduate student reports:

Participating in the affinity group during the past two courses has allowed for a disruption of the systemic experiences that I have experienced. It was a welcome change that is needed and should be incorporated into all administrator license programs.

We can no longer ignore and perpetuate those elements of our program that stifle student learning and development or, worse, cause or exacerbate mental and physical health issues in our students. With the effects of racial microaggressions (Sue et al., 2007) and the resulting racial battle fatigue (Smith, 2016) for students of color laid bare, the positive psychological and physiological benefits of processing and discussing content through racial affinity groups seem clear. Using racial affinity groups as an instructional practice in graduate courses is a simple strategy that can yield significantly beneficial results.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

Beatriz Desantiago-Fjelstad, EdD

Bernadeia H. Johnson, EdD

Melissa Krull, PhD

Joel Leer, PhD

ISSN: 2998-8470

DOI: https://doi.org/10.62889/2024/dbkl1203

eLocator: dbkl1203