| Caitlin Johnson1, PhD | Department of Leadership & Learning, Minnesota State University, Moorhead1-4 |

| Brian Johnson Jr.2 | Student Research Assistant |

| Madalyn LaVallie3 | Student Research Assistant |

| Darla Warren4 | Graduate Student Research Assistant |

We have no known conflict of interest to disclose. We would also like to acknowledge and give thanks to our financial contributor of the Minnesota State University Moorhead Foundation (Dille Fund for Excellence), in which the grant served to both incentivize the survey and provide stipends to create the first 100\% indigenous-led research team on campus. Miigwech (Thank you).

In Fall 2023, the Equity Score card for Minnesota State University Moorhead (MSUM) indicated the largest equity gap is among Indigenous students totaling 25.4% and was widening the last three years. The Indigenous student success rate from fall to fall first year completion was 57. l %. As a result, this study was conducted to implement a supplemental survey to the Campus Climate Survey in Spring 2023. MSUM students who identified as Indigenous students in their admissions paperwork were targeted for this study to better identify the needs of indigenous students at the university. After identifying the needs, we can better support Indigenous students on campus in hopes of closing the equity gap.

The survey of indigenous students achieved a 40.3% completion rate of the total population of indigenous students at MSUM. The findings revealed the academic, cultural, and health needs of the indigenous students who participated in the survey. The data analysis indicated the following: (1) Indigenous students predominantly identified as non-traditional and working class; (2) symptoms of anxiety and depression were high with noted perceptions that higher education had a significant influence on individual mental health; (3) indigenous students at MSUM were more likely to note additional educational barriers (4) students’ self-disclosed terms for their identities varied which potentially skews institutional data to not represent the larger number of students with indigenous identity; and (5) basic needs of indigenous students were not being met. The results of this study can be used to address the current gaps in the statistics that often “other” the indigenous student voices that have been noted as “lack of sample size.” The voices of this survey can help to further expose why the equity gap is the largest among Indigenous students, but also help educators/institutions to identify ways they can provide more support.

Keywords: Indigenous Populations, Inclusion, College Environment, Educational Indicators, and Student RetentionStatistically, Native American students comprise 1.1% of the undergraduate and graduate student population in the United States. Post-secondary data often leaves Native students out of the research—noting a small sample size (Postsecondary National Policy Institute, 2021). Often, the lack of data and representation of Indigenous people in academia is one of the underlying reasons why this demographic often goes commonly overlooked. This has served as reasoning why interventions aren’t used to recruit and retain Indigenous students in higher education–we are not considered a “significant” population in higher education.

According to the United States Census (2018), Native Americans have the highest poverty rate among all minority groups. The corresponding years later, the data report given by the U.S. Census no longer listed Native Americans as a recognized special category population (Asante-Muhammad et. al., 2022). These statistics, or lack thereof, arguably make the case for an education system that is more responsive to the specific needs of Native American students (Johnson, 2023). The underrepresentation is just one reason why we need to take a deeper look at the root cause–why is the population so small and what can we do to better support them in their pursuit of education? There’s power in education–it helps to create economic opportunities for students. When, arguably, Native Americans see the highest poverty rates among any other demographic group in our nation, how can we not address the elephant in the room? That the idea of lack of data and representation are pointing toward a flawed educational system–one that further marginalized Indigenous people.

Furthermore, the classification system that lumps those who may be of “mixed” heritage in another demographic entirely (often classified under ‘multiple races’) has also added to this invisibility in data. Indigenous students who self-disclose “multiple races” in demographic or admissions data are often overlooked as something else entirely. As a result, many institutions have a larger Indigenous student population that we have initially been led to believe.

We often look to the numbers in education–we like data. We want to know what educational systems and educational methods are working; we look to the numbers to help provide us with information to be more meaningful with our approaches to education. Meaning–we examine the numbers and the statistics to support that additional support is needed. But what happens when those numbers are absent due to lack of sample size? According to the Minnesota State Equity Scorecard (2023), a 25.4% equity gap among Native American students was identified. An educational equity gap refers to disparities in educational outcomes and student success across a variety of different demographic factors (such as race, disability, socioeconomic status, etc.). This equity gap had widened over the last three years prior to 2023 and the Native American student success rate from fall to fall first year completion was 57.1%. The Minnesota Equity Scorecard is “an instrumental tool for creating greater awareness of, and accountability for, equity gaps across key facets of our institutions and system which are relevant to impacting equity, diversity, and inclusion using measurable key performance indicators” (Minnesota State, 2024). Currently, the widest equity gap in the state of Minnesota is with indigenous populations. Arguably, the lack of sample size for indigenous populations in higher education helps to expose the equity gap.

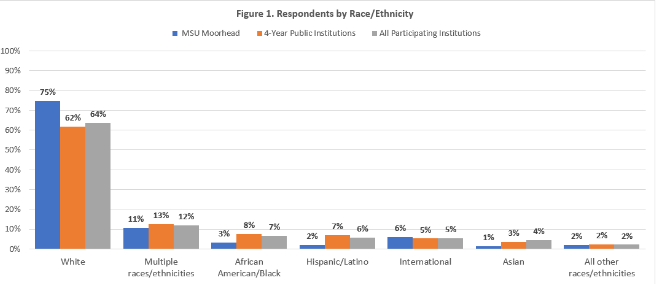

In the Spring of 2023, our university conducted its first Campus Climate survey. A Campus Climate survey is an instrument that gains insights into the student experiences on campus to better understand and improve campus climate regarding various diverse topics. Figure 1 below was taken from the preliminary data from the Campus Climate survey in our first year.

For this interpretation, it is listed as those that only marked one race would fall in the single identity category with another category being listed as “Multiple races/ethnicities.” This category in addition to the predominantly “White” category, the other listed categories listed are “African American/Black, Hispanic/Latino, International, Asian, and Other. Yet again, othering Native American/Indigenous students.

Additionally, there are arguments that state the “othering of an entire demographic (such as Indigenous people) is a contemporary form of racism still present in society today. According to Rebecca Nagle (2018), she states:

Invisibility is the modern form of racism against Native people. We are taught that racism occurs when a group of people is seen as different, as other. We are not taught that racism occurs when a group of people is not seen at all. Yet the research shows that the lack of exposure to realistic, contemporary, and humanizing portrayals of Native people creates a deep and stubborn unconscious bias in the non-Native mind. Rooted in this unconscious bias is the idea that Native people are not real or even human.

The othering of the Indigenous population in the Campus Climate survey data and the continued dismal of the statistics for “lack of sample size” can further support the argument of the shortcomings of higher education institutions for not addressing the equity issue for its current state. We must continue to ask ourselves the questions: Why are Indigenous populations not pursuing higher education opportunities, why are they less likely to return for their second year at university, and what can we do to better support Indigenous students. These are the million-dollar questions, but often do not get addressed or ever asked enough in predominantly white institutions. In order to provide equitable access to higher education for all, we must ask these questions and look directly to the student population for the answers.

In a quest for answers to these questions, one story came to mind as we embarked on this research project. Shawn Wilson (2008) in his book, Research is Ceremony, tells the story of the coyote who goes to college and majors in Native American Studies. After going to all of his classes, he realizes every teacher is a non-Native teaching from a non-Native book. So, he did not want to bother continuing his studies from the school he was attending, because he wanted to learn Native American studies from a Native American source (Wilson, 2008, p. 3-6). Wilson uses the coyote story to develop his theme that much of the knowledge given to students from university about Native Americans can be one-sided. Wilson later illustrates how the coyote goes from class to class in search of being taught Native American Studies from an Indigenous person, however the coyote cannot find a professor who is Indigenous or uses a book written by an Indigenous author. As a result of the coyote’s failed attempts to locate a native voice in academia, he decides to drop out of college. This is not uncommon for Indigenous people in academia, as less than one-half of 1% of all full-time faculty of colleges and universities are Indigenous (National Center for Education Statistics, 2024). Thus, it is more challenging to see ourselves in higher education. Wilson leaves the moral of the story up to us as the reader; however, we believe it shows the further oppression of Native American people by articulating that the knowledge passed to people from academic institutions is given very one-sided and not using the indigenous voice to benefit the Native American populations. For these reasons, the indigenous voice and stories cannot be overpowered by the broader population. We need to look directly at the population to best determine their needs. In the quest for social justice in education and to help eliminate the equity gap, we fight with, not for Indigenous students in academia.

As we began to plan for this research project, we looked to other Indigenous scholars to help inform our conceptual framework for our study. During the initial planning stages, we found the work of the National Resource Center on Indigenous Aging (NRCNAA) to be highly informative. The NRCNAA is funded by the Administration for Community Living under tribal Title VI programs through the Department of Health and Human Services. The NRCNAA conducts a health and social needs assessment every 3 years and has worked with over 300 tribes since 1994. The original purpose of the survey by the University of North Dakota was to assess the health and social needs of the Indigenous population of elders. We found this survey to be closely related to what we were examining in our own study—a self-disclosure of the needs of a specific Indigenous demographic. The survey instrument used by the NRCNAA study consists of self-reported (Indigenous elders) information related to general health status, activities of daily living, health care access, weight & nutrition, and demographics. The primary questions used in this study were health status, history of chronic disease, nutritional health, participation in cultural practices, and demographic variables that include gender, age, marital status, income, employment, and education (Adamsen, 2018). We looked to the questions related to cultural practice, basic needs, and demographic variables to be the correlating questions that we also wanted to measure as part of our MSUM Native American Student Needs Survey. Like the Indigenous elder survey, we wanted a measurement of the needs of an indigenous population that could help to inform our practice, but also serve as an opportunity to gain necessary research to help demonstrate the need for specific programming or grants.

The survey was designed to examine MSUM Native American students’ perceptions of attending higher education, determine existing best practices, and identify ways that MSUM can offer additional support for Indigenous students. Multiple variables were examined using specific sections in the survey:

The survey was distributed online using Qualtrics with password protected encryption given to current MSUM students. An analysis using appreciative inquiry, along with statistical analysis was utilized. Appreciative inquiry empowers its practitioners to explore innovative practice while being an agent of change by challenging the dominant power (Hung et al., 2018). It is an approach that “has the potential to address gaps in knowledge by revealing ways to take action” (Hung, Phinney, Chaudhury, Rodney, Tabamo, & Bohl, 2018, p. 1). Cram (2010) states that appreciative inquiry has “transformational elements…[that] reside in its claims that it generates new knowledge and that is results in generative metaphors that compel new action” (p. 2). It is believed that appreciative inquiry “offers a positive way to explore, discover possibilities, and transform systems” working toward a shared vision (Hung et al., 2018, p. 2). This analysis was selected as it allows us to recognize the things our institution is doing well, while also pointing out the gaps in which we can improve.

This was a case study research design. Sample size consisted of students who self-identified as indigenous students in their admissions paperwork (including those who identified as “multicultural” or “multiple races” with indigenous affiliations. Surveys were administered to students at the beginning of September 2023 and closed after a period of eight weeks. Informed consent was given at the beginning of the survey with the arrow to the next page as an implied consent as a research participant. There was an incentive that was offered to participants through the opportunity for a raffle. The raffle was for one of twenty possible $25 Walmart gift cards. During the distribution of the online survey, it was explained to the possible participants that an incentive raffle would be conducted at the end of the data collection. Those who participated in the survey/interview would enter the raffle as a thank you for their participation. Once a participant completed the survey, it would redirect them to a different online survey for their name, phone number, and email address to be put in for the raffle. This information was not linked to their previous survey, so it protected the confidentiality of their original responses. Their contact information was only used to contact the winners of the raffle at the end of the data collection process. It was later determined that not every student entered their information as part of the gift card incentive process, however they still chose to participate in the survey cycle. Overall, the survey was administered to current MSUM indigenous students to examine if students’ basic and cultural needs are being met in addition to their academic needs.

To understand the needs of indigenous students (and the overall population), we must first understand historical trauma and its influence on learning. Historical trauma refers to “community massacres, genocidal policies, pandemics from the introduction of new diseases, forced relocation, forced removal of children through Indian boarding school policies, and prohibition of spiritual and cultural practices” (Evans-Campbell, 2008, p. 316). As we reflect on historical trauma, we need to consider the impact of boarding school trauma on Indigenous people and how it has influenced education. Whether we want to acknowledge it or not, historically education has been part of a system that has contributed to the erasure of an entire culture—from our history to the native voices. It has ultimately contributed to the distrust that Indigenous people have had in the educational system (including that of higher education). Furthermore, Intergenerational trauma transmission of trauma is, “from person to person or within communities and gives us little insight into the relationship between historical and contemporary trauma responses” (Evans-Campbell, 2008, p. 316). Meaning, we may not have lived through the boarding school era ourselves, but the stories and its history continue to have a lasting impact on our generation today. However, merely acknowledging that this history has happened isn’t enough.

Currently, cultural awareness is a buzz word in teaching and learning. However, cultural awareness doesn’t go far enough in supporting indigenous students, especially in a higher education classroom where they are the minority. Focusing on cultural safety as practice would be considered best practice. When we approach indigenous students with cultural awareness, we simply just acknowledge that a student has a cultural identity that may differ from our own. When we approach our students with cultural sensitivity in mind, we are taking the necessary steps to consider our own cultural identity and experiences to determine how they can impact others. Best practice is cultural safety, which is when students perceive us as “safe” and “not a threat” to their own cultural identity being accepted in the classroom (Tujague et al, 2021). When we are making sure our classrooms are culturally safe with trauma informed practices, we are making sure that we are providing a place for healing to happen— starting by centering indigenous voices in academia. It starts by getting to know their individual stories. Practicing cultural safety is looking beneath the surface to examine the nuances of the student’s identity (simply bringing in an indigenous author as a text doesn’t go far enough). We need to take special considerations in how the student identifies, including their tribal affiliations (i.e. not all Ojibwe people will identify with an author who is Navajo, as it is a tribe other than their own).In King’s (2005) book The Truth about Stories: A Native Narrative, he speaks of the importance of stories and how they come to shape who we are as Native American people. These stories hold a valuable part of our identity as Native American people to share history, values, and lessons of our culture. In order for us to support indigenous students in academia, we must start this work by listening—we listen to the stories of our indigenous students and share a mutual respect of one another. We show our interest in their stories, experiences, and background. It can start in the classroom with something as simple as an entrance survey to get to know your students and taking the time to take note of each of the identities present in your course.

Healing begins when we share our stories and experiences, which helps us to understand the trauma we have suffered from in the past and present (Johnson, 2023). While we must acknowledge that historical trauma has influenced our learning, so have our contemporary forms of trauma (i.e. prejudice, harassment, or microaggressions are all forms of contemporary trauma experiences). According to MSUM’s Campus Climate survey, approximately 12% of survey respondents have experienced discrimination or harassment, while 7% are unsure. Other students are identified as the primary source of discrimination or harassment 73% of the time, followed by faculty, staff, community and administrators. Students as a source is a higher percentage at MSUM than at 4-year public institutions and all participating institutions. These are just one form of modern-day forms of trauma that can have an overall effect on learning. Thus, often than not, indigenous students have compounded trauma (both historical and contemporary) that has contributed to their overall learning experiences. If we wish to address the equity issue, given what we know about Indigenous people and history, we must do it with trauma informed practice. When we are making sure that our institutions are culturally safe with trauma informed practices, we are making sure that we are providing a place for healing to happen—which ultimately creates a welcoming atmosphere and promotes inclusion. Healing begins when we share our stories and experiences in education, which helps us to understand compounded trauma. As practitioners, understanding how trauma of indigenous students has led to social, emotional, and economic disadvantage helps us to move past racist assumptions (Tujague et al, 2021). Moreover, “trauma- informed education is intimately connected with equity and justice” (Imad, 2022). Once this deeper reflection and understanding takes place in higher education environments, we can move forward to becoming agents of change in higher education. Additionally, this approach to education is often connected with cognitive brain theory, as when we experience social rejection (both real and perceived), it can put an additional stressor on our brains (Imad, 2022). When we have negative stressors on our brains, it can affect our ability to learn and process information, which is why we are led to believe the notion of Maslow’s hierarchy of needs to hold merit.

The traditional understanding of human needs, as conceptualized by Abraham Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, has been widely accepted and applied across various fields. However, this framework has often been criticized for its universalistic approach, overlooking cultural variations in the understanding of needs. Bear Chief et al. (2022) argue that the hierarchy may not fully capture the holistic nature of human needs, particularly within Indigenous communities. They propose alternative frameworks that prioritize relational and spiritual needs alongside physical and psychological ones.

First Nations’ perspectives on the hierarchy of needs emphasize interconnectedness, community, and spirituality as central to human well-being, which contrasts with Maslow’s individualistic approach. Within First Nations’ worldviews, the self is intricately connected to the community and the natural world. Therefore, the fulfillment of one’s needs is often intertwined with the well-being of the collective. This communal orientation challenges Maslow’s emphasis on individual self-actualization and suggests the importance of considering collective well-being in any model of human needs.

Reconsidering Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs from a First Nations’ perspective reveals the limitations of universalistic frameworks in capturing the complexity of human needs. By centering Indigenous worldviews, we gain insights into the interconnectedness of human existence, the importance of community and spirituality, and the holistic nature of well-being. Moving forward, it is essential to incorporate diverse cultural perspectives to develop more inclusive and contextually relevant models of human needs.

Institutions in higher education are seeing more of a push in diversity, equity, and inclusion (or DEI) work. If they wish to truly provide an equitable environment for all and advance racial equity, we must examine educational barriers (including those of ensuring students’ basic needs). If the self-actualization tier is indigenous students graduating with a degree, what are the basic needs that they have in order to help them achieve it? As part of our attempt to strive for advancing racial equity to help identify barriers, the research team developed a Native American Student Hierarchy of Needs based on the findings of this study (listed above) in hopes for practitioners to better understand the complex needs of this demographic group in education.

In addition to determining basic needs to help identify potential barriers that affect indigenous student success, the survey proved to be beneficial to the addition of the Campus Climate Survey. A finding of this study was that the Native American student population were primarily transfer students at 60.71%. Additionally, approximately 60% of students also identified as non-traditional students (i.e., students older than 24 years of age, delayed college enrollment after high school, attended college part time, works full time, financially independent from parents, has dependents, and/or have no high school diploma). There was also a higher-than-average first-generation student rate at 55.56%. Approximately 75% of all respondents indicated they worked full or part-time in addition to attending classes. This coincided with higher numbers of students needing childcare and financial strain attending university with 18.4% working full-time to help cover tuition costs and at least one student identified as homeless.

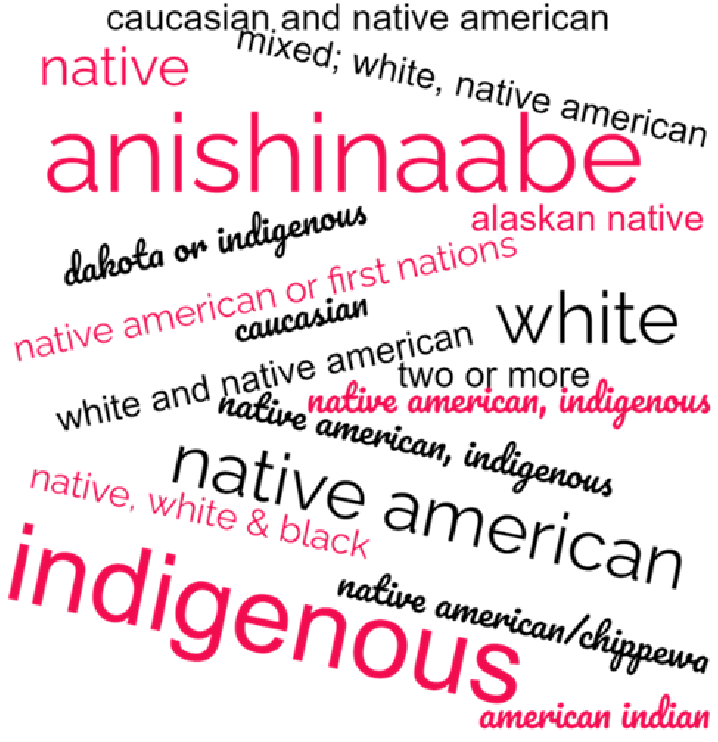

In addition, there was a self-disclosure of cultural terms question included, as there were beliefs that our campus demographic numbers may not have been as accurate as believed due to students marking “other” or “multiple races” as a demographic indicator.

In Figure 3, we compiled a word cloud using all the self-disclosed terms used to describe their cultural background. Students who indicated “white” as their preferred term also indicated in their responses that they were Indigenous people but didn’t “grow up with indigenous traditions” and/or “didn’t know a lot about the background” so they felt uncomfortable to describe themselves as any other term. Many students identified as multiple races at approximately 53.70%. Thus, reinforcing the idea that our campus numbers may not be as accurate as we perceive them to be.

The questions also revealed that not only do most consider their higher education experience “very good”, but their higher education experience also holds great value for their overall demeanor and feelings of oneself with only 5.66% stating school had no effect on their mental health. While the overall satisfaction in higher education experiences was high, there were higher needs in mental health and basic needs of students (such as getting enough food or sleep). As is highlighted in Table 1.

| Variables | Responses | % |

| During the past month, how much of the time were you a happy person | All the time | 1.89 |

| Most of the time | 28.30 | |

| A good bit of the time | 35.85 | |

| Some of the time | 22.64 | |

| A little bit of the time | 9.43 | |

| None of the time | 1.89 | |

| During the past month, how much of the time did you feel calm and peaceful | All the time | 1.89 |

| Most of the time | 13.21 | |

| A good bit of the time | 28.30 | |

| Some of the time | 35.85 | |

| A little bit of the time | 18.87 | |

| None of the time | 1.89 | |

| During the past month, how much of the time have you felt anxious or nervous | All the time | 9.43 |

| Most of the time | 32.08 | |

| A good bit of the time | 26.42 | |

| Some of the time | 18.87 | |

| A little bit of the time | 11.32 | |

| None of the time | 1.89 | |

| During the past month, how much of the time have you felt depressed | All the time | 1.89 |

| Most of the time | 13.21 | |

| A good bit of the time | 11.32 | |

| Some of the time | 28.30 | |

| A little bit of the time | 32.08 | |

| None of the time | 13.21 | |

| How often do you feel you are getting enough sleep | All the time | 0.00 |

| Most of the time | 18.87 | |

| A good bit of the time | 15.09 | |

| Some of the time | 33.96 | |

| A little bit of the time | 18.87 | |

| None of the time | 13.21 | |

| How often do you feel you are getting enough to eat | All the time | 11.32 |

| Most of the time | 33.96 | |

| A good bit of the time | 22.64 | |

| Some of the time | 18.87 | |

| A little bit of the time | 9.43 | |

| None of the time | 3.77 |

In addition to demographic and health findings of this study, a significant finding was that for a call for more culturally responsive events and education. Table 2 shows their responses to these series of questions.

| Variables | Responses | % |

| Participates in cultural practices on or off campus | Yes | 59.26 |

| No | 18.52 | |

| Never hear of any off campus | 22.22 | |

| Participates in traditional dancing | Yes | 22.22 |

| No | 77.78 | |

| If no to traditional dancing, would you benefit from learning it | Yes | 52.38 |

| No | 16.67 | |

| Undecided | 30.95 | |

| Access to traditional regalia | Yes | 44.44 |

| No | 55.56 | |

| If no to traditional regalia, would you benefit from making on campus or from the community | Yes | 83.33 |

| No | 16.67 | |

| Do you currently participate in any campus student organizations or clubs (such as the AISA) | Yes | 26.00 |

| No | 38.00 | |

| I want to, but I often work or cannot attend | 36.00 | |

| Do you attend the activities during Native American heritage month | Yes | 19.61 |

| No | 31.37 | |

| I want to, but I often work or cannot attend | 49.02 | |

| Do you enjoy participating in any of the cultural events on campus | Yes | 41.18 |

| No | 3.92 | |

| I have never attended one | 54.90 |

As previously stated, while there were not high attendance numbers for certain campus events, Native American students wanted accessibility to traditions and cultural teachings. Students shared that they wanted access to cultural events to build community and belonging on campus, but also wanted access to traditional ceremony. As this is a key piece in mental and spiritual health for indigenous people, there is a correlation between these two findings of our study.

In addition to the Likert scale questions, we also created open-ended questions where students typed out their responses to further explain their experiences and needs. If students indicated fair or poor for their experiences in higher education, we asked them to explain their response. The following four responses were collected: (1) “I believe that my experience would be better if the education was less expensive to reach.” (2) “I have faced lots of different adversities and hard times while enrolled at MSUM. I have been working very very hard to stay enrolled at MSUM and have appealed suspension two times.” (3) For me I feel like it all happens too fast, and I feel like I don’t have time.” & (4) “It is ok never above average.” These responses reinforced some of the findings of the demographic data, such as the mental health and financial barriers indicated by participants.

As previously stated, while there were not high attendance numbers for certain campus events, Native American students wanted accessibility to traditions and cultural teachings. Students shared that they wanted access to cultural events to build community and belonging on campus, but also wanted access to traditional ceremony. As this is a key piece in mental and spiritual health for indigenous people, there is a correlation between these two findings of our study.

In addition to the Likert scale questions, we also created open-ended questions where students typed out their responses to further explain their experiences and needs. If students indicated fair or poor for their experiences in higher education, we asked them to explain their response. The following four responses were collected: (1) “I believe that my experience would be better if the education was less expensive to reach.” (2) “I have faced lots of different adversities and hard times while enrolled at MSUM. I have been working very very hard to stay enrolled at MSUM and have appealed suspension two times.” (3) For me I feel like it all happens too fast, and I feel like I don’t have time.” & (4) “It is ok never above average.” These responses reinforced some of the findings of the demographic data, such as the mental health and financial barriers indicated by participants.

The research team also wanted to ask participants about the type of cultural events they would like to see on campus as part of their cultural support on campus. The results demonstrated a trend for a call for more programming across campus, specific activities listed were powwow, traditional indigenous ceremony, cultural learning activities (especially from those who felt disconnected from their traditional culture), community partnership events, family meal style events (including traditional meals and frybread feeds), drum circles, traditional art and craft nights, community-based education using traditional knowledge systems of elders as teachers, storytelling, learning to dance traditionally and regalia making, and indigenous language camps. These findings also reinforce the demographic questions in the survey that inquired about cultural events on campus and accessibility to cultural art forms (such as traditional dancing or regalia).

Whether it be the lack of accessibility or the lack of time, indigenous students identified that barriers did indeed exist in their pursuance of being involved in campus events or student organizations/clubs. Students were asked if they did not attend any campus events or were not involved in any student organizations/clubs, what keeps them from participating. A major finding in this area was that the additional barriers that indigenous students have in their daily lives prohibited them from attending. The responses ranged from they were too busy with other commitments, doing homework, family obligations including caring for their child/ren or other family members, lived too far from campus or were an online student, have increased anxiety increased in social situations, or they are working. One participant stated, “My mom is hospitalized at Mayo in Rochester most of this semester, I’m here with her.” as an additional hardship that added to their participation in school/cultural events.

Whether it be the lack of accessibility or the lack of time, indigenous students identified that barriers did indeed exist in their pursuance of being involved in campus events or student organizations/clubs. Students were asked if they did not attend any campus events or were not involved in any student organizations/clubs, what keeps them from participating. A major finding in this area was that the additional barriers that indigenous students have in their daily lives prohibited them from attending. The responses ranged from they were too busy with other commitments, doing homework, family obligations including caring for their child/ren or other family members, lived too far from campus or were an online student, have increased anxiety increased in social situations, or they are working. One participant stated, “My mom is hospitalized at Mayo in Rochester most of this semester, I’m here with her.” as an additional hardship that added to their participation in school/cultural events.

In hopes to better support indigenous students, participants were asked if they could give any advice about supporting Native American students. The responses varied and included the following: providing more support to Native American clubs and affinity groups on campus, providing more cultural activities, assistance/support for online/virtual learners, assistance with FAFSA and the campus scholarship system, providing more scholarship opportunities for diverse students, community partnerships, as well as improved outreach to help recruit and retain Native American students. One participant stated that “As a culture, we usually keep to ourselves because we feel like outsiders off of our reservations/hometowns. MSUM should make it a point to get to know ALL attending tribal members and to ALWAYS make them feel included and their voice always heard.” This statement and others echoed that universities need to be intentional in the recruitment process and retention of their indigenous students. This intentionally working with indigenous students should not only be culturally responsive but can help create/build lasting relationships to help students feel heard and supported in higher education.

While it is considered best practice to compensate individuals from marginalized groups who participate in a study, it also has the potential to create additional barriers. We compensate individuals to thank them for their time dedicated to their participation and add incentive, however it is an additional barrier with the growing issue of bots in the online survey world. We learned that due to the issue of bots, we did have to wipe our system of surveys and add an additional protection of an added password. Due to this step, some responses were potentially lost due to the changes and corrections in the survey collection protocol.

In addition to creating survey protocols for bots (like adding a password that you provide targeted participants); the research team would advise others who wish to implement a Native American Student Needs Survey at their institution to include transportation questions as part of the survey. Transportation was an identified gap in the data after the survey was administered. Disability Support Services was identified as a support service not listed in the response matrix, so this should also be added.

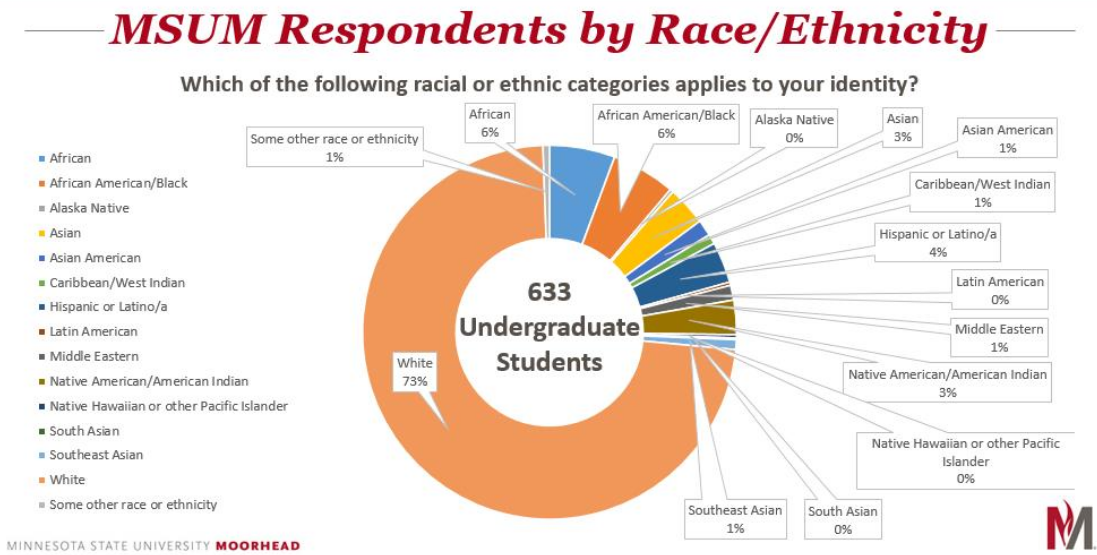

The voices of this survey can help to further expose why the equity gap is the largest among Native American students, but also help educators/institutions to identify ways they can provide more support. This survey provided insight into the Native American student population on the MSUM campus. The insight gained, can help pave the way forward in broadening the Native American student body at MSUM. The support by staff, faculty, and administration at MSUM for this study spoke volumes their respect towards the Native American community we have on our campus. Our voices are being heard and that is a step in the right direction. Many Native American students at MSUM were heard and represented via the MSUM Native American Student Needs Survey. The importance of being heard has always been at the forefront of Native American people. Not only were they heard and represented, but the results will help guide the path going forward for MSUM to help eliminate the equity gap. Furthermore, it can also serve as a framework for transparency of data with minority populations as well, since “othering” can be harmful. As a result of the preliminary findings of both this study and the campus climate data, the university worked on creating more transparency of data working with minority populations, which includes the following graphic:

This type of work was more intentional in terms of breaking down additional demographic information with highlighting marginalized campus community voices. The updated graphic in comparison to Figure 1 in this article highlights the intentionality behind data transparency. It takes more steps but can help to expose institutional and systemic gaps present in higher education. While the research in this study centered on highlighting indigenous voices, the work on our study also made contributions to the overall campus climate framework for data transparency.

This work is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0

eLocator: e1803